GITR Research in Tumor Immunotherapy

Investigation into new potential targets for tumor immunotherapy has been ongoing now for over a decade. One protein that has long been studied in this framework is GITR (TNFRSF18), a member of the TNF superfamily of proteins that is expressed on T cells. Its ligand, GITRL, is expressed on antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells. This pathway modulates the T cell immune response through a dual mechanism1 that primarily enhances the proliferation of regulatory T cells (Tregs)2 and also enhances the metabolism of effector T cells3. Because of these dual effects, understanding how best to target GITR in the setting of immunotherapy has remained challenging. Luckily, advances have recently been seen, and the stimulatory effect on regulatory T cells does not appear to be a factor in the cancer setting.

Various GITR agonists are used to target this pathway for therapeutic purposes. In a study of multiple murine tumor models, a GITRL fusion protein was delivered in conjunction with a tumor vaccine. Depending on the tumor model, monotherapy with the fusion protein or combination with the vaccine led to an increase in the number of tumor-specific effector T cells and a depletion of Tregs. Additionally, this treatment increased the levels of GITR on tumor-specific effector T cells, making this population of cells more responsive to treatment4. In a similar study, antibody-induced agonism of GITR increased the proliferation, interferon gamma production, and glycolysis of effector T cells in both the tumor microenvironment and draining lymph node of a tumor3. Most importantly, GITR agonism in combination therapy leads to tumor eradication or delayed tumor progression5. Another role of GITR agonist antibodies is the depletion of Tregs, and this has been shown in both murine tumor models and human tumor models in humanized mice6, 7. The specific population of Tregs that appears to be depleted by this treatment is a highly suppressive subtype that expresses both CD44 and ICOS. Depletion of Tregs, in turn, allows intratumoral T cells to downregulate expression of PD-1 and LAG3 to become more effector-like7.

Besides impacting T cells, GITR agonism also affects B cells, and this effect is crucial for therapeutic efficacy. In a mouse model, treatment with an agonistic antibody targeting GITR led to an increase in B cell activation, differentiation, and production of antibodies. Most importantly, B cells were required for this treatment to have any effect on effector T cells, as shown in B cell depletion studies8.

More recently, GITR agonism has made its way into the clinic. The anti-GITR antibody MK-4166 is in clinical trials as both a monotherapy and a combination therapy with checkpoint blockade for solid tumors, including melanoma9. An earlier clinical trial using a different anti-GITR antibody, TRX518, as a monotherapy depleted both circulating and intratumoral Tregs and increased the ratio of effector to regulatory T cells in patients with various solid tumors. However, clinical responses including changes in tumor burden or survival were not observed. This antibody is now in clinical trials in combination with anti-PD-110. With the recent migration of GITR from the lab to the clinic, yet with questions still to be answered about the basic biology of targeting this pathway, studying GITR in the context of cancer immunotherapy remains an exciting and valuable area of research.

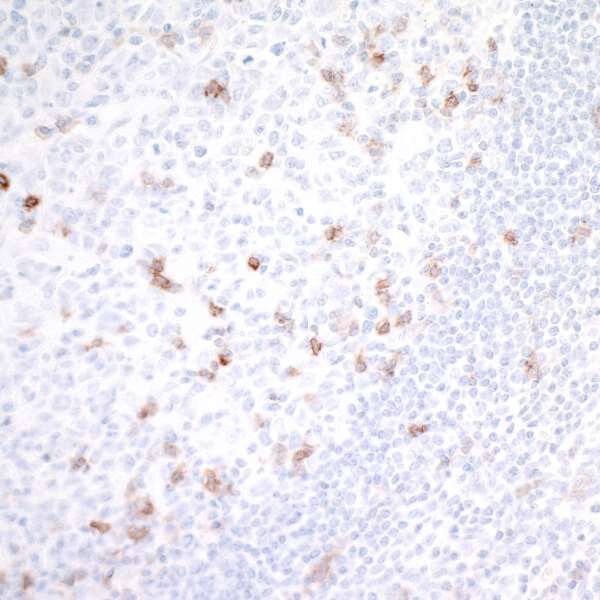

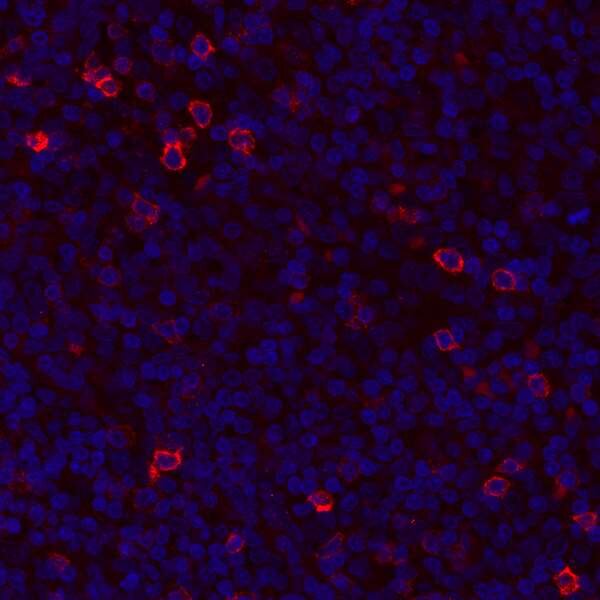

Detection of human GITR/TNFRSF18 in FFPE tonsil by IHC. Antibody: Rabbit anti-GITR/TNFRSF18 recombinant monoclonal [BLR068G] (A700-068). Secondary: DyLight® 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (A120-101D4). Counterstain: DAPI (blue).

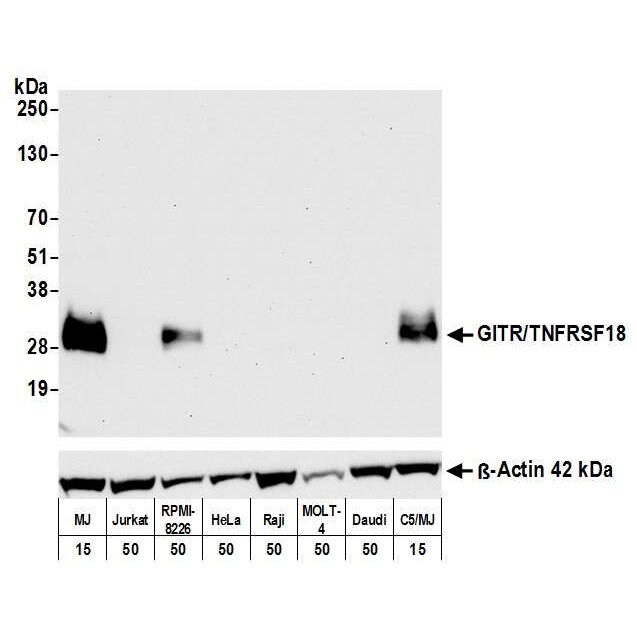

Detection of human GITR/TNFRSF18 by WB of MJ, Jurkat, RPMI-8226, HeLa, Raji, MOLT-4, Daudi, and C5/MJ lysate. Antibody: Rabbit anti-GITR/TNFRSF18 recombinant monoclonal [BLR068G] (A700-068). Secondary: HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (A120-101P). Lower Panel: Rabbit anti-ß-Actin recombinant monoclonal antibody [BLR057F] (A700-057).

References

- Shevach EM, Stephens GL (2006) The GITR–GITRL interaction: co-stimulation or contrasuppression of regulatory activity? Nat Rev Immunol 6:613–618 . doi: 10.1038/nri1867

- Liao G, Nayak S, Regueiro JR, Berger SB, Detre C, Romero X, de Waal Malefyt R, Chatila TA, Herzog RW, Terhorst C (2010) GITR engagement preferentially enhances proliferation of functionally competent CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Int Immunol 22:259–70 . doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq001

- Sabharwal SS, Rosen DB, Grein J, Tedesco D, Joyce-Shaikh B, Ueda R, Semana M, Bauer M, Bang K, Stevenson C, Cua DJ, Zúñiga LA (2018) GITR Agonism Enhances Cellular Metabolism to Support CD8 + T-cell Proliferation and Effector Cytokine Production in a Mouse Tumor Model. Cancer Immunol Res 6:1199–1211 . doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0632

- Durham NM, Holoweckyj N, MacGill RS, McGlinchey K, Leow CC, Robbins SH (2017) GITR ligand fusion protein agonist enhances the tumor antigen–specific CD8 T-cell response and leads to long-lasting memory. J Immunother Cancer 5:47 . doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0247-0

- Hoffmann C, Stanke J, Kaufmann AM, Loddenkemper C, Schneider A, Cichon G (2010) Combining T-cell Vaccination and Application of Agonistic Anti-GITR mAb (DTA-1) Induces Complete Eradication of HPV Oncogene Expressing Tumors in Mice. J Immunother 33:136–145 . doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181badc46

- Coe D, Begom S, Addey C, White M, Dyson J, Chai J-G (2010) Depletion of regulatory T cells by anti-GITR mAb as a novel mechanism for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 59:1367–1377 . doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0866-5

- Mahne AE, Mauze S, Joyce-Shaikh B, Xia J, Bowman EP, Beebe AM, Cua DJ, Jain R (2017) Dual Roles for Regulatory T-cell Depletion and Costimulatory Signaling in Agonistic GITR Targeting for Tumor Immunotherapy. Cancer Res 77:1108–1118 . doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0797

- Zhou P, Qiu J, LʼItalien L, Gu D, Hodges D, Chao C-C, Schebye XM (2010) Mature B Cells Are Critical to T-cell-mediated Tumor Immunity Induced by an Agonist Anti-GITR Monoclonal Antibody. J Immunother 33:789–797 . doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181ee6ba9

- Papadopoulos KP, Autio KA, Golan T, Dobrenkov K, Chartash E, Li XN, Wnek R, Long G V. (2019) Phase 1 study of MK-4166, an anti-human glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor (GITR) antibody, as monotherapy or with pembrolizumab (pembro) in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 37:9509–9509 . doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.9509

- Zappasodi R, Sirard C, Li Y, Budhu S, Abu-Akeel M, Liu C, Yang X, Zhong H, Newman W, Qi J, Wong P, Schaer D, Koon H, Velcheti V, Hellmann MD, Postow MA, Callahan MK, Wolchok JD, Merghoub T (2019) Rational design of anti-GITR-based combination immunotherapy. Nat Med 25:759–766 . doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0420-8