LAG3 and T cell exhaustion

Normally, T cell activation leads to clonal expansion and acquisition of effector function, allowing cytotoxic T cells to lyse target cells and mount an effective immune response. However, in situations where T cells are exposed to a specific antigen for an extended period of time, such as in chronic viral infection or cancer, T cells can become dysfunctional as a result of antigen desensitization. Dysfunctional T cells multiply inefficiently, progressively fail to produce cytokines, and ultimately become ineffective at killing target cells.1 This process of antigen desensitization and subsequent dysfunction is known as T cell exhaustion, and illustrates a particular challenge in the immune response to chronic viral infection and cancer.

The molecular signature of exhausted T cells was first described in 2007,2 and multiple molecules involved in promotion of T cell exhaustion have since been described. Among others, these molecules include cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3).1

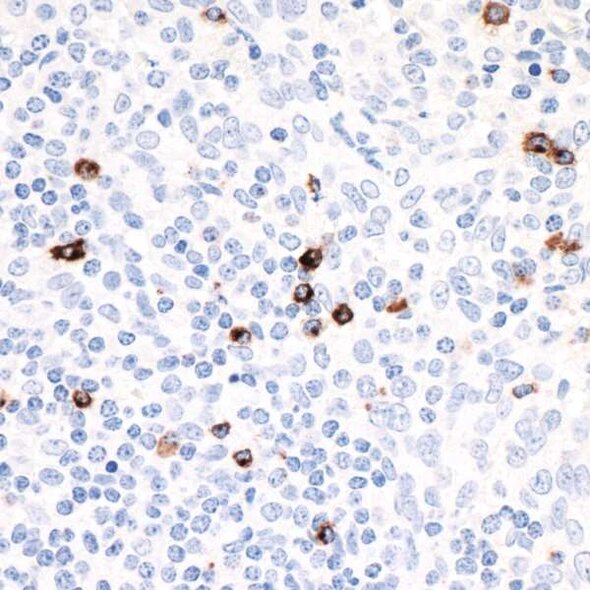

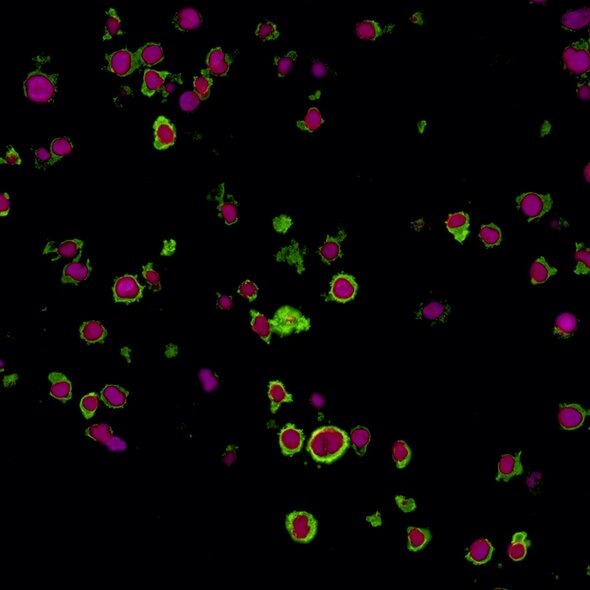

LAG-3 is found on the cell surface of cytotoxic and regulatory T cells and is an immune checkpoint receptor protein that controls T cell activation and growth.3 LAG-3 is not expressed in resting T cells, but is upregulated after T cell activation in an effort to prevent autoimmunity.4 LAG-3 efficiently inhibits the immune response by binding major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II), which in turn inhibits T cell activation and growth.4 Expression of LAG-3 is associated with compromised antigen-specific T cell function in humans with cancer and chronic infection, but LAG-3 blocking antibodies can restore exhausted T cell function in animal models and in cultured human cells.5,6 Due to its role in regulating T cell exhaustion, LAG-3 represents a potential target for development of therapeutic agents in cancer and chronic infection.

In cancer, exhausted LAG-3-expressing cytotoxic and regulatory T cells accumulate at tumor sites,7 and in preclinical studies, LAG-3 inhibition allows for T cells to regain their cytotoxic function and subsequently decrease tumor growth.8 Clinical trials investigating LAG-3 blockade, alone or in combination with PD-1 blockade, are ongoing.9 This dual targeting of complementary immune pathways may represent a more effective strategy to reactivate previously exhausted immune response than a therapy which targets only a single receptor. In addition, clinical trials targeting a soluble form of LAG-3 which exhibits immune adjuvant activity, potentially through affecting the LAG-3/MHC-II interaction, are also underway.9

Continued development of clinical anti-LAG-3 therapies may provide a novel treatment option for patients with cancer or chronic viral infection by effectively activating (or more accurately, reactivating) the anti-tumor immune response.

Bethyl offers the following LAG-3 antibodies:

References

- Wherry EJ. 2011. T cell exhaustion. Nature Immunol. Jun;12(6):492-499.

- Wherry EJ. 2007. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. Oct;27(4):670-684.

- Durham NM, Nirschl CJ, Jackson CM, et al. 2014. Lymphocyte Activation Gene 3 (LAG-3) modulates the ability of CD4 T-cells to be suppressed in vivo. PLoS One. Nov 5;9(11):e109080.

- Workman CJ, Rice DS, Dugger KJ, et al. 2002. Phenotypic analysis of the murine CD4-related glycoprotein, CD223 (LAG-3). Eur J Immunol. Aug;32(8):2255-2263.

- Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, et al. 2006. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. Feb 9;439(7077):682-687.

- Matsuzaki J, Gnjatic S, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, et al. 2010. Tumor-infiltrating NY-ESO-1-specific CD8+ T cells are negatively regulated by LAG-3 and PD-1 in human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. Apr 27;107(17):7875-7880.

- Camisaschi C, Casati C, Rini F, et al. 2010. LAG-3 expression defines a subset of CD4(+) CD25(high) Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells that are expanded at tumor sites. J Immunol. Jun 1;184(11):6545-6551.

- Grosso JF, Kelleher CC, Harris TJ, et al. 2007. LAG-3 regulates CD8+ T cell accumulation and effector function in murine self- and tumor-tolerance systems. J Clin Invest. Nov;117(11):3383-3392.

- Clinicaltrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine (US). Accessed 2018 June 7. Available from: ClinicalTrials.gov results for LAG-3.