Mechanisms of Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy

Efforts to harness the immune system for management of cancer were first undertaken in the last 1890s,1 but these therapies were initially disregarded in favor of more consistently effective treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Since then, multiple pioneering experiments have advanced understanding of tumor immunobiology and spurred development of cancer immunotherapies,2 several of which have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. These immunotherapies shift the focus of cancer treatment away from the tumor itself, and rather toward the patient’s immune system. These therapies may induce the immune system to act directly against the tumor (i.e., checkpoint inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, adoptive cell transfer, treatment vaccines), or may enhance the body’s anti-cancer immune response (i.e., cytokines).

One appealing feature of cancer immunotherapy is the durability of treatment response, owing to the memory of the adaptive immune system. Unfortunately, though, only a subset of patients experience this durable response, since many fail to respond to immunotherapy altogether (primary resistance), or initially respond to treatment but later relapse (adaptive resistance). Primary and adaptive immune resistance can also manifest as acquired resistance, in which cancer cells adapt to protect themselves from immune attack. Primary and adaptive mechanisms of resistance to immunotherapy may be intrinsic or extrinsic to tumor cells.

Tumor cell-intrinsic mechanisms of primary or adaptive resistance to immunotherapy include 1) an absence of antigenic mutations, thereby preventing recognition by T cells;3 2) alteration of antigen-presenting machinery or antigen-associated transporters in order to avoid presenting these antigens;4,5 3) exclusion of T cells from the vicinity of cancer cells;6 and 4) inability of T cells to recognize cancer cells, such as through mutations in the interferon gamma pathway.7

Tumor cell-extrinsic mechanisms of primary and adaptive resistance to immunotherapy involve components of the tumor microenvironment other than the actual tumor cells. These components include regulatory T cells, cytokines, macrophages, and other inhibitory immune checkpoints. Tumor cell-extrinsic mechanisms of resistance to immunotherapy include 1) an absence of necessary T cells, such as those with the tumor antigen-specific T cell receptor; 2) inhibitory immune checkpoints (i.e., V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation [VISTA], lymphocyte-activation gene 3 [LAG-3], T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 [TIM-3]); 3) release of cytokines or metabolites (i.e., transforming growth factor beta [TGF-β], adenosine); 4) and immunosuppressive cell populations such as regulatory T cells or macrophages.8

Efforts to identify reliable biomarkers or predictors of resistance to immunotherapy are ongoing. A greater understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying resistance should enable subsequent development of therapies to overcome this resistance and expand the benefits of cancer immunotherapy to a wider patient population.

Bethyl offers a wide variety of antibodies for cancer research.

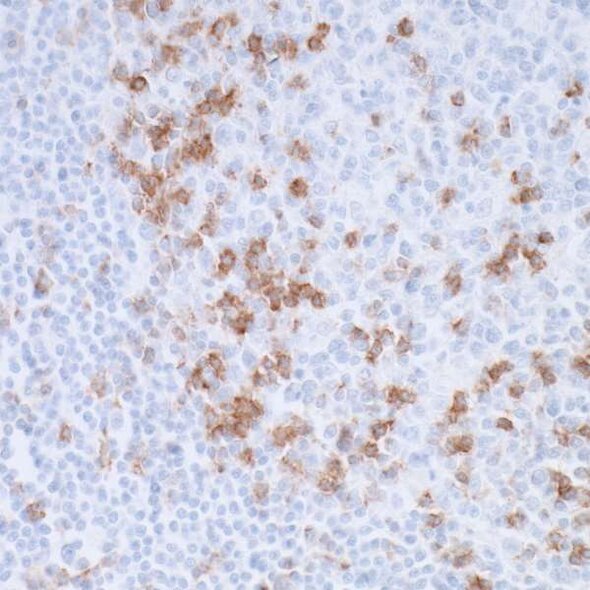

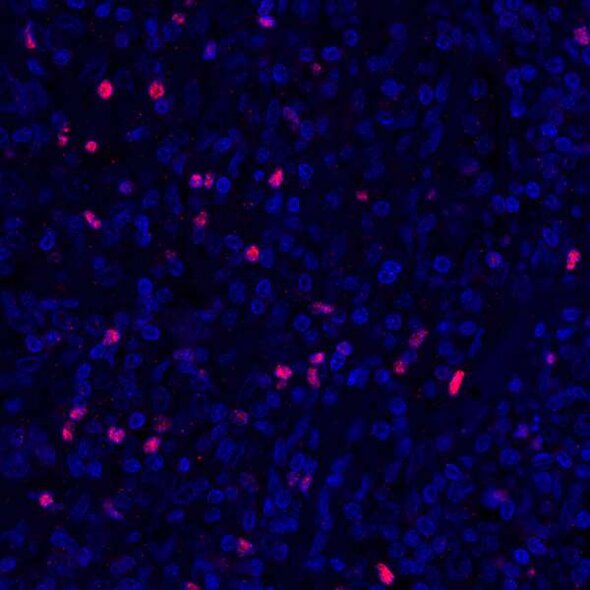

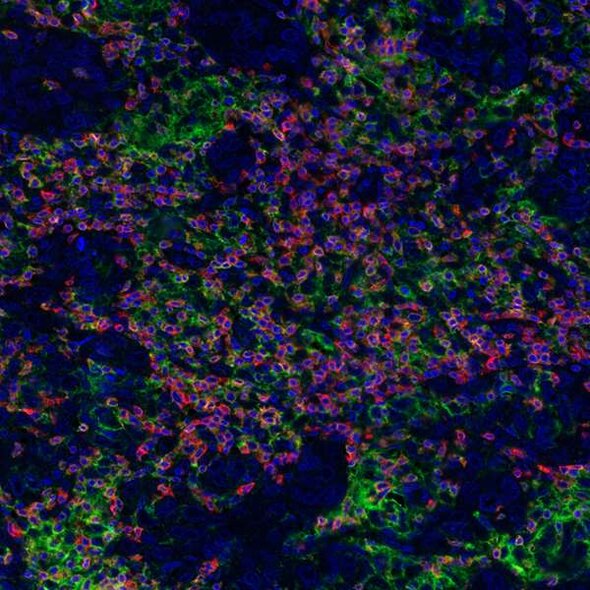

Detection of human CD3E (orange), CD8 alpha (red), and PD-L1 (green) in FFPE breast carcinoma by IHC-IF. Rabbit anti-CD3E recombinant monoclonal [BL-298-5D12] (A700-016), rabbit anti-CD8 alpha recombinant monoclonal [BLR044F] (A700-044), rabbit anti-PD-L1 recombinant monoclonal [BLR020E] (A700-020). Secondary: HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (A120-501P). Substrate: Opal™ 520, 620, and 690. Counterstain: DAPI (blue).

References

- Coley WB. 1910. The treatment of inoperable sarcoma by bacterial toxins (the mixed toxins of the Streptococcus erysipelas and the Bacillus prodigiosus). Proc R Soc Med. 1910;3:1-48.

- Tran E, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA. 2017. ‘Final common pathway’ of human cancer immunotherapy: targeting random somatic mutations. Nat Immunol. Feb;18(3):255-62.

- Gubin MM, Zhang X, Schuster H, et al. 2014. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature. Nov;515:577-81.

- Marincola FM, Jaffee EM, Hicklin DJ, et al. 2000. Escape of human solid tumors from T-cell recognition: molecular mechanisms and functional significance. Adv Immunol. 2000;74:181-273.

- Sucker A, Zhao F, Real B, et al. 2014. Genetic evolution of T-cell resistance in the course of melanoma progression. Clin Cancer Res. Dec;20(24):6593-604.

- Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. 2015. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signaling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. Jul;523:231-5.

- Gao J, Shi LZ, Zhao H, et al. 2016. Loss of IFN-gamma pathway genes in tumor cells as a mechanism of resistance to anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Cell. Oct;167(2):397-404.e9.

- Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, et al. 2017. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell. Feb 9;168(4):707-23.