TIM-3 for a Change

Immune-checkpoint inhibitors is a popular topic of current discussion within the realm of tumor therapeutics. Most notably cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) have garnered the most attention. The first immune checkpoint inhibitor associated with overall survival within a phase 3 metastatic melanoma study, Ipilimumab, is a fully humanized antibody against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associate-d antigen 4 (CTLA-4) antibody.1,2 Blockade of PD-1 has achieved revolutionary clinical impact in many solid cancers; however, there has been certain roadblocks which have prevented full response to anti-PD-1 therapy.3-5 A significant percentage of cancer patients fail to respond to these therapies due to compensatory immune inhibitory pathways.6

TIM-3 is now

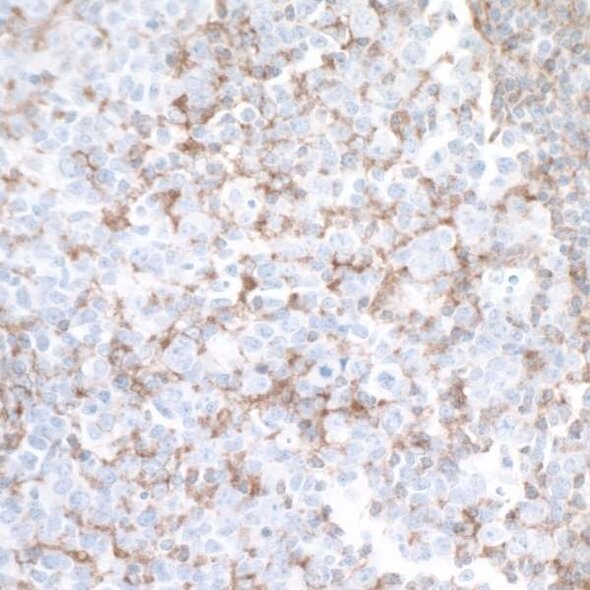

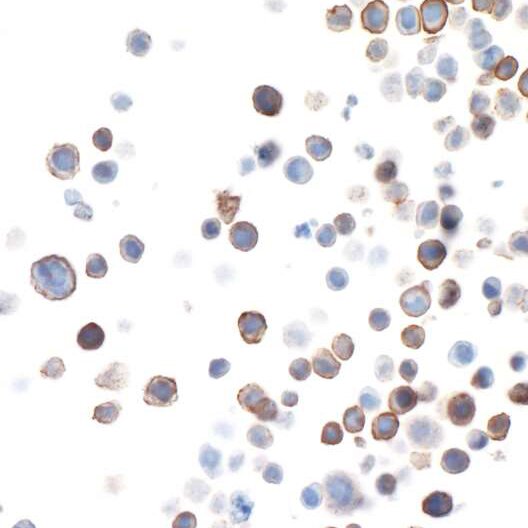

In 2016, Koyama and colleagues compared the immune cells present in effusion samples collected from patients whom developed resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy with that of immune cells from five patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who had not received anti-PD-1 treatment.7 Higher levels of TIM-3 were detected in T cells from the PD-1 resistant patients compared with the other patients.7 T-cell immunoglobin mucin-3, TIM-3, is highly expressed on tumor infiltrating dendritic cells and actively competes with nucleic acids released from dying tumor which effectively inhibits stimulation of the innate immune response by nucleic acids.6,8 This weakening of innate immunity by TIM-3 exposes a major vulnerability in which tumor cells are now able to bypass pro-inflammatory cytokines. In addition, TIM-3 inhibits immune responses and promotes tolerance by regulating multiple targets including CD4+ T, CD8+ T, T-regulatory (Tregs), Forkhead Box P3 (FoxP3), Type 1 regulatory T (Tr1), Natural killer (NK), dendritic (DCs), and myeloid-derived suppressor (MDSCs) cells.9 Such findings suggest the therapeutic targeting of TIM-3 within the context of cancer. However, due to its extensive role in immune response, TIM-3 mAbs can also influence other pathophysiological mechanisms such as the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE).10 In addition, administration of TIM-3 mAbs has found to not inhibit tumor growth on its own.11 Therefore, careful thought on how and when to use TIM-3 mAbs should be considered.

A Compromise

In 2010, it was shown that combination of TIM-3 and PD-1 mAbs had a much greater antitumor effect than administration of TIM-3 or PD-1 mAbs alone.11 Therefore, a two-tier therapeutic model in which CTLA-4 and PD-1 represent the first tier of co-inhibitory receptors that are primarily responsible for maintaining self-tolerance and the second tier which includes TIM-3 as a co-inhibitory molecules that regulates immune responses at sites of tissue inflammation has been introduced as an alternative resolution to resistance.9 As expected, the effect of PD-1 blockade is proportionally larger than that of Tim-3 blockade alone. However, Tim-3 blockades preferentially affect tumor tissue Treg and IL-10-producing Tr1 cells while additionally affecting dendritic cell phenotype and dampening MDSCs. Thus, there has been a consensus that different checkpoint receptor blockades can be combined to achieve distinct effects on the immune response.9

References

- Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003466

- Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O’Day S, Weber J, Garbe C, Lebbe C, Baurain J-F, Testori A, Grob J-J, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(26):2517–2526. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1104621

- Dong H, Zhu G, Tamada K, Chen L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nature Medicine. 1999;5(12):1365–1369. doi:10.1038/70932

- Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, Tykodi SS, Sosman JA, Procopio G, Plimack ER, et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(19):1803–1813. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1510665

- Romero D. Immunotherapy: PD-1 says goodbye, TIM-3 says hello. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2016 Mar 15 [accessed 2018 Jul 2].

- Du W, Yang M, Turner A, Xu C, Ferris RL, Huang J, Kane LP, Lu B. TIM-3 as a Target for Cancer Immunotherapy and Mechanisms of Action. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017 [accessed 2018 Jul 2];18(3). doi:10.3390/ijms18030645

- Koyama S, Akbay EA, Li YY, Herter-Sprie GS, Buczkowski KA, Richards WG, Gandhi L, Redig AJ, Rodig SJ, Asahina H, et al. Adaptive resistance to therapeutic PD-1 blockade is associated with upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints. Nature Communications. 2016;7:10501. doi:10.1038/ncomms10501

- Tang D, Lotze MT. Tumor immunity times out: TIM-3 and HMGB1. Nature Immunology. 2012;13(9):808–810. doi:10.1038/ni.2396

- Anderson AC. Tim-3: An Emerging Target in the Cancer Immunotherapy Landscape. Cancer Immunology Research. 2014;2(5):393–398. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0039

- Monney L, Sabatos CA, Gaglia JL, Ryu A, Waldner H, Chernova T, Manning S, Greenfield EA, Coyle AJ, Sobel RA, et al. Th1-specific cell surface protein Tim-3 regulates macrophage activation and severity of an autoimmune disease. Nature. 2002;415(6871):536–541. doi:10.1038/415536a

- Sakuishi K, Apetoh L, Sullivan JM, Blazar BR, Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207(10):2187–2194. doi:10.1084/jem.20100643